3/5/2018

by Braxton Crewell and Michael Guy

Since its first performance in 1604 at the Whithall Banqueting House in London, productions of Othello have reflected the cultural traditions and prejudices of their times.

During the 17th century, Othello and Desdemona were played by white men. Richard Burbage was the leading tragedian of Shakespeare’s company and played Othello, while a younger man played Desdemona. It wasn’t until after the English Civil War that women were allowed on the stage, and in 1660 Margaret Hughes was the first female Desdemona.

In the 18th century, James Quin emphasized the professionalism of a dignified general by wearing a British military uniform with a powdered wig, while David Garrick presented an anxious and taut Othello in an elaborate turban — and both were white actors who performed in blackface. John Philip Kemple portrayed a majestic and stately Othello, which was initially unpopular as this went against a common idea of the day that Africans had trouble controlling their passion and vigor. Nonetheless, he continued with this choice and by the late 18th century when he revived the show opposite his sister, Sarah Siddons, people had grown fond of this “European and reasonable” Othello.

In the early 1800s, Edmund Kean revolutionized the image of Othello, becoming the “Tawny (light-skinned) Othello.”

Ira Aldridge, an American teenager who moved to London to established himself as an actor in 1824, became the first black professional actor to play Othello. He was billed as the “Gentleman of Colour,” and claimed to be Senegalese royalty rather than a kid from New York City, hoping it would fascinate audiences and make them come to the show. It worked.

Edwin Forrest, the first American Othello, brought animalistic qualities to the role in 1840, perpetuating negative generalizations audiences had of the relationship between race, morality, and temperament. Forrest was famous for blackface performances and his caricatures of African-Americans.

In 1930, Paul Robeson, the American singer and civil rights activist, was the second black man to play Othello in a London production. Robeson changed the typical portrayal from a psychological drama to an actual tragedy turning on racial conflict. His dignified but ultimately defenseless Othello in the face of a malignantly racist Iago, garnered much popularity with audiences. When his production transferred to Broadway in 1943, Robeson and his co-star Uta Hagen shared the first interracial kiss on a major American stage.

Up until the late 1960s, many white actors were still portraying Othello, including John Gielgud, Michael Gambon, and Laurence Olivier. Olivier would return to the role in a film adaptation, which was much acclaimed in its day, but it was later scrutinized for its traditional use of blackface.

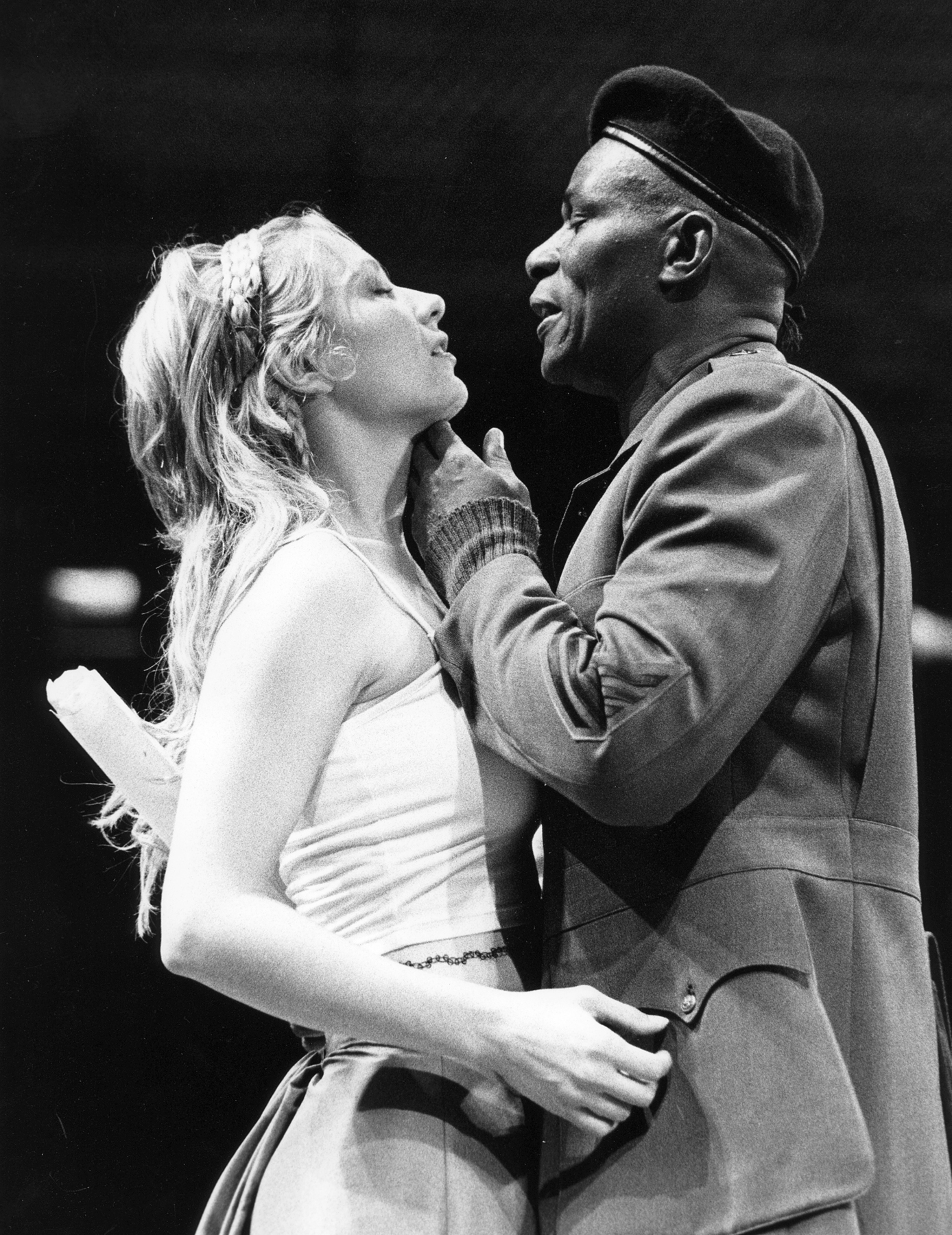

James Earl Jones took up the mantle of Othello on Broadway in 1982, bringing a “mountain of strength” to the role. His Othello was thwarted by a masterful portrayal of Iago by Christopher Plummer.

In 1987, John Kani, a Tony Award-winning South African actor, performed Othello in the first professional production in apartheid South Africa to feature a black actor in the title role. It was directed by Janet Suzman, perhaps South Africa’s best-known actress at the time, and Iago was also portrayed by a black actor. One more twist — in 1997 Patrick Stewart starred in a “photo-negative” production in which Othello was white in an otherwise predominantly black cast